Does motorsport, car control, skidpan training make drivers safer on road?

Everybody wants safer drivers, right? And a common refrain from motorsport people, of whom I am one, is that the way to achieve that is to teach better car control. How to handle a car, recover from a skid and so on.

There’s very few things which are completely black and white in the automotive world, and this subject isn’t one of them. There will be times when skilled application of opposite lock will save the day, and teaching vision, looking up, is a huge help.

But I’m yet to see any data that car control skills, dancing the car through cones and the like, actually has any measurable effect on reducing accident rates. Instead, I see the opposite; every study I’ve read says such training either doesn’t help, or increases the risk of a crash through overconfidence. You can see some links and excerpts at the end of this article.

So let’s go to the data and look at the most common accident type. In 2014 AAMI released some stats saying about 30% of claims were from nose-to-tail. How would advanced car control help there? You might argue people could brake better, but surely it’d be better to observe what’s happening beforehand and just brake earlier? Another 20% were parking dings, and another 20% ‘failed to give way’ another observation-related incident. We’re up to 70% now, add another 11% for reversing, and collision with a stationary object at about 15%. Data out of the USA broadly agrees with the Australian figures – citing 11% for t-bone crashes.

So if we take a risk-based approach, and what other way is there to do it, then you’d want to focus on why people crash. And the way to avoid all of those listed is not finely-honed, edge-of-traction car control, it’s observation of what’s happened and early reaction to it. Even low-frequency, high-impact crashes such as running off the road are observation-related; if you come too hot into a corner on a public road, then your fate is often sealed and no amount of correction can save you, public roads have oncoming traffic and runoff areas are rare, unlike a racetrack where you have space to gather up your car. Why too hot in? Mindset, and/or lack of observation. Everyone drives safely with a police car behind them, don’t you think?

Who would you rather ride with, a drift and stunt king who reacts at the very last second, or someone whose idea of a cool car is a Camry but they’re so alert they’re reacting to situations before you’ve even noticed them?

Now in motorsports one thing we do focus on is vision, as in looking ahead. Many, many problems on the racetrack can be traced back to not looking far enough ahead, and the same concept can be applied to road driving. But there are differences.

On a racetrack, you’re really just looking to position the car, monitor entry, apex, exit. Vision is about the car position on the track, and even if you’re racing and need to observe what’s happening ahead, it’s quite different to the road, it’s a relatively simple environment. “Look where you want to go” is what we say for racetrack training – consider entering a fast left-hand sweeper – you would not be looking to your right, whereas in road driving, you would need to be 360 degrees aware of your situation.

On the road looking ahead applies (in addition to sideways and behind) but it’s more about interpreting what you see and translating that understanding into action; far more complex than hotlapping where it’s the same corners every ninety seconds and not much to do other than place your car. And on road it could be about looking behind you, and to the sides. You don’t need to do that so much on a racetrack.

Now as I said advanced car control skills are definitely helpful on road. I’m sure people will comment saying they saved this that or the other, and I can also point to my own experience too. But in every case I could have done better and avoided the situation. Oh and being self-critical is part of being a good driver, even if you weren’t at fault or had right of way, what could you have done better, or would you prefer “I was right” on your tombstone?

Then we come to the “well just in case you need the skills” argument and again I agree, but the problem is developing the skills and maintaining them. Go to any racetrack and you’ll see people who own track or racecars losing control all the time..and if these people can’t control a car, and they’re clearly into it…what hope for the average punter? You can go to a car-control class and, by the end of the day, probably hold a drift, kinda-sorta. Great, that’s when you’re freshly trained, after 25 tries, for a few seconds. Now will you still have those skills six months later, in a different car, when you’re not expecting it? I would suggest not, those skills are perishable, and there’s less need for them with modern cars. How so?

Consider a wet evening. You’re cruising along at 80, sightly downhill, and the road curves left. Suddenly you notice traffic has come to an unexpected stop. You’ve left braking a bit late, but you can still stop in time if you’re good.

If you were driving a car from the ’70s your skills would be very well tested. If you jumped hard on the brakes you’d most likely lock a wheel and understeer off the road. So you’d need to modulate the brakes, know how to fractionally release the pressure soon as the wheels lock. Could well be the back end starts to step out too, so you’d have to correct that with steering. All in all, that sort of maximum-traction stop on a wet, fast, downhill curve would test even a good driver.

Today the picture is different. All you need to do is slam your foot on the brake pedal, and more or less steer. ABS will stop the wheels locking, and give you back as much grip as you need to turn. EBD will apportion braking force front and rear. And if you haven’t hit the brakes hard enough, EBA will add some extra braking force for you. ESC will take care of the car spinning out, no need for oversteer correction. And even lane keep assist will note the roadlines and gently nudge the car into line. And that’s just the active safety features. I haven’t even covered CBC either. The summary is – car control skills are needed even less today than they were back in the day.

And what about the people who say “but I had a near-accident with <stupid driver> and there was nothing I could do, lucky I had my skillz”. Well, what if the other driver was very aware, observing things and reaching appropriately? Then they wouldn’t have done the stupid thing.

Yet for all that I do think motorsport and car control training has a place in road safety training, but it’s not a huge part of the answer, and such skills can turn an average-but-safe driver into a very skilled, mechanically sympathetic and very safe driver.

The real skill is observing what’s happening in a complex road traffic situation, and translating that into action – again, look at the stats I quoted.

It’s really important when “driver training” is discussed that everyone is clear about the type of training – both racetrack training and low-risk training are advanced, post-licence training, but with very different methods and results. The former shaves tenths of a second off laptimes, the latter reduces road accident rates.

For example, this report describes two types of training – one focused on skid control, i.e. taking reacting after the event, and the other on avoidance. It describes the avoid-training as effective, and the react-training as ineffective.

Good road drivers use their above-average observation to avoid situations where their above-average car control skills are not needed. Yes, pilots will recognise that one!

Some report extracts:

Although some portion of teenage crash involvements can be accounted for by poorer basic vehicle handling skills, the research suggests that it is young drivers’ immaturity and inexperience, and the resultant risk-taking, that contribute most to their increased crash risk.

—Teenage Driver Risks and Interventions, Scott V. Masten, January 2004.

Low risk on-road behaviour basically requires three things:

- the acquisition of necessary skills

- the ability to apply these skills efficiently and effectively when operating on the road and in traffic

- the willingness or motivation to apply these skills when operating on the road and in traffic

When trying to place a framework on novice driver safety, the interplay of the following global factors should receive consideration:

- the skilled performance literature indicates that novices perform significantly worse than their more experienced counterparts for a variety of reasons associated with the nature of information processing

- there is mounting evidence that the riskiness of novice driver driving cannot be fully explained by skill decrements and that there is a motivational component contributing to their over-representation in accident statistics.

….evidence in the area serves to further reinforce the view that novice driver safety has two, complementary aspects – the skills-based and the motivational and that safety improvements can potentially be derived from both.

–AN OVERVIEW OF NOVICE DRIVER PERFORMANCE ISSUES: A LITERATURE REVIEW: Alan Drummond

In a previous study, it is well documented that adolescents are more likely than adults to engage in risky behaviour (Arnett, 1992). Most evidence suggests that risk-taking is the most important major factor underlying the high crash rates among teens.

— The Relationships between Demographic Variables and Risk-Taking Behaviour among Young Motorcyclists Siti Maryam Md and Haslinda Abdullah

There is no sound evidence that either advanced or defensive driving courses reduce the crash involvement of experienced drivers who attend them

— RACV

High teen crash risk is due to a number of factors, including (obviously) a fundamental lack of driving skill. However, contrary to what one might think, the evidence suggests that poor vehicle control skills account for only 10% of novice driver crashes; the remaining 90% is accounted for by factors such as inexperience, immaturity, inaccurate risk perception, overestimation of driving skills, and risk taking (Edwards, 2001).

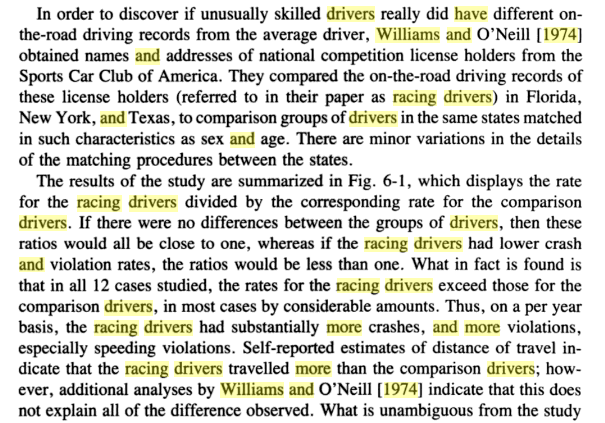

Evidence shows that in the USA the highest skilled drivers (registered race and rally car drivers) have a much higher crash rate than the average driver (Naatanen and Summala, 1976).

… alleged benefits [of skidpan training] rest upon the assumption that a substantial proportion of crashes are attributable to a lack of vehicle-control skills: increased exposure to assorted manoeuvres on a skidpan will improve these skills and thus reduce accidents. However, again the evidence does not stand up to close examination: attendance at skid training programs has increased rather than reduced crash involvement (Langford, 2002, P.36).

An analysis of accident and conviction data for a two year post-training period showed no statistically significant differences between any of the groups, (ie trained vs. untrained young drivers)

Strang, Deutsch, James & Manders (1982) A comparison of on-road and off-road driver training. A comparison of novice driver training Road Safety & Traffic Authority.

Post Licence driver education and driver improvement programs have shown no differences between drivers who have completed the program and those who had not.

Circosta and Salotti (1990) A review & discussion of issues related to the training and education of novice drivers. Brisbane; Road Safety Division, QLD Transport.

Driver and rider training programs have suffered over recent years from the fact that many skilled and careful evaluations have shown little effect, none, or even a negative effect on accident rates when it has been employed.

Henderson (1991) Education, publicity and training in road safety; A literature review.

Racing drivers, young drivers and male drivers, the very groups with the highest levels of perceptual-motor skills and the greatest interest in driving, are the groups which have the higher than average crash involvement rates. This demonstrates that increased driving skill and knowledge are not the most important factors associated with avoiding traffic crashes. What is crucial is not how the driver can drive (driver performance) but how the driver does drive (driver behaviour).”

The clear failure of the skill model underlines the need to consider motivational models that incorporate the self-paced nature of the driving task.

Leonard Evans (1991) Traffic Safety & The Driver

In our view, the increased accident frequency of the racing (trained) drivers is not due to their superior driving but can be more likely contributed to a greater-than-average acceptance of risk, which induced them to pick up the activity of car racing to begin with.

Offers such as track days giving youngsters the chance to drive quickly in safe conditions would need to be considered very carefully and we strongly advise you need to further examine the available evidence in greater detail before proceeding with these ideas. Norwegian studies from 15-20 years ago (reported in Tronsmoen 2008) found an increased accident rate from people who had been on skid courses – probably because of over-confidence.

Courses have been trialled extensively in the U.S., taught by police or specific driving schools, however a number of studies (U.S., Norway) indicate that young drivers who joined these courses went on to have higher crash rates than those who did not (Jones, 1993; Glad, 1988). Williams and Ferguson (2004) attribute this to inspiring overconfidence and/or that tempt young people to try out the manoeuvres, while Horswill et al (2003) suggest that raising people’s estimations of their hazard detection skills through hazard perception improvement interventions may cause them to drive more riskily because they think they can handle the risk better.

Encouraging Road Safety Amongst Young Drivers: How can Social Marketing Help?

“There is little evidence that courses teaching advanced driving manoeuvres such as skid pan control improve driver safety, and they can produce adverse outcomes”

(Williams and Ferguson 2004, p.4) Wilde GS (1994) Target Risk

“These results suggest that a high level of driving skill is associated with a high crash risk. This apparent contradiction could be explained as follows: the belief of being more skilled than fellow drivers increases confidence in one’s abilities more than it increases actual abilities. A high confidence in one’s abilities could lead to an aggressive style of driving that could lead to more critical situations.” OECD (1990) Behavioural adaptations to change in the road transport system. Road Transport Research.

A recent review of pre-driver training and education found no evidence to support the presumption that such programmes directly improve driver safety (Kinnear et al., 2013). While there was some evidence of short-term attitudinal change, the vast majority of programmes are not evaluated sufficiently, or at all, to determine if this is a consistent finding.

http://www.roadsafetyobservatory.com/HowEffective/drivers/driver-training

—Traffic Safety & the Driver, Leonard Evans