Electric vehicle realities & myths

Many people are have a negative view of EVs based on incorrect, or outdated information.

Conversely, some pro-EV people will take any fact or viewpoint that isn’t absolutely pro-EV and try and argue it away whilst claiming if only we all drove EVs the world’s problems would be solved, and any problems with a move to EVs are trivial.

So now I’ve upset both sides of the argument, there’s a middle ground, and that’s what I’m trying to address in this post and my videos below. Based on many comments and conversations, here’s a list of things not well understood about EVs:

- EVs are not yet cost effective compared to ICE cars for the majority of owners. The price difference is often far too great for comparable models, and the lower run costs don’t make up the difference unless you factor in pro-EV assumptions such as hugely better resale for EVs than ICE, lots of EV-friendly mileage, or zero-cost electricity which usually ignores the cost of infrastructure such as solar to get that low cost. But, it’s getting closer and closer and soon, EVs will become the sensible, cost-effective choice for the average driver. EVs won’t need to sell for the same buy price as ICE to be a better 5-year ownership cost because their run costs are much lower – fuel and servicing, so the longer you own your car and the more mileage you do, the more cost-effective an EV becomes.

- There is little need for public charging – realistically, if you just do daytrips and around-town errands or commutes, you can do all your charging at home off your standard 240v – most cars are idle at home for the majority of their life, and many city owners very rarely use any public chargers. So public charging infrastructure is much less of a problem that first thought.

- EVs are superb tow vehicles, but not for long distances so they can’t yet do the job of a diesel 4×4. I have towed with a Tesla, went very well…briefly, and also carried out what may be the world’s most detailed diesel/EV tow test. Right now, EVs are good for short-range towing as they’re powerful, heavy and slow down nicely under regen, but no good for towing long distances as their range suffers greatly. Many of my readers/followers/viewers own drive and tow long distances, as do I – I write this in a caravan I towed from Melbourne to NSW, a journey of 9 hours I did on a single (long-range tank) fuel fill, so this is important to us. More here:

- Even with ‘dirty’ the electricity, the modern EV is still better for the environment. In short, petrol/diesel requires a lot of effort to extract, then transport, refine, transport again – compare that to electricity which, once created even by coal, costs very little to transport. And you can generate electricity in many places thanks to renewable tech. Also, ICE cars don’t convert much of the energy in a given quantity of fuel to propulsion – an EV converts around 80% of its energy to propulsion, an ICE only around 25% as a lot of the energy is lost in heat, and some more in friction due to all the moving parts. But that ignores build lifecycle, so…

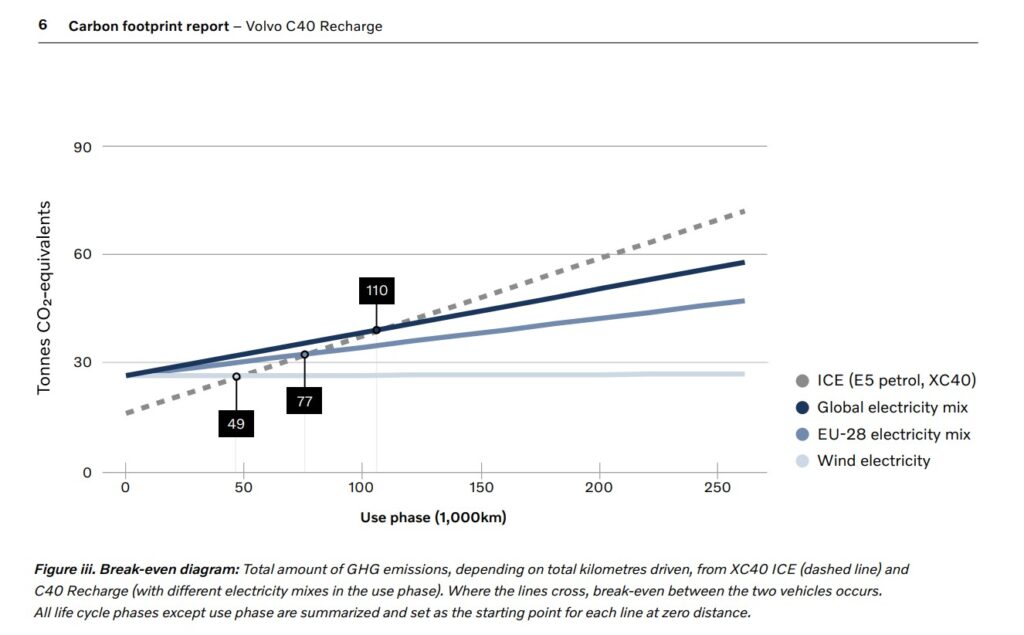

- Are EVs better overall for the environment? Almost always, yes and it’s improving. Basically, creating an EV generates more emissions than an ICE due to the battery manufacturing, at the moment. However, once the cars are in use, the EV has far less emissions, possibly zero depending on how the electricity it uses is generated. So, at some point the EV is overall better for emissions. The ‘some point’ is variable; depends on many factors such as the size of the battery, how the EV’s electricity is generated and so on. Here’s an example graph from Volvo showing one of their ICE cars vs their EV, with three different EV lines reflecting different electricity generation scenarios:

- Old EV batteries aren’t wasted. This is one area the EVs haven’t been great, but now EV batteries are recycled as there’s a real incentive given the precious metals involved. Australia now has the capability to completely recycle EV batteries – you can’t recycle petrol or diesel, it gets burned. Modern EVs have battery management systems which ensure the battery is operating in the right temperature zone and that prolongs its life. The Kona battery (see videos below) is warranted for 8 years. And, even if the batteries aren’t recycled they may be re-used for home battery systems where you charge the battery from renewable sources and draw down the power as required.

- Batteries don’t need replacing; Tesla and others are looking at lifetime batteries built into the chassis of the car, so no replacement, and ‘lifetime’ means at the moment 8 years or 240,000km with 70% capacity (Tesla), and in the future, up to 1.6 million km. How many modern ICEs are going to last that long without major rebuild work? None, I’d suggest.

- Update your EV assumptions – tech changes…you can’t compare a first-gen Nissan Leaf of 2010 (117km range) with a 2021 Hyundai Kona EV (484km range) any more than it’s fair to compare an aged LandCruiser 60 Series with a modern 300 Series. But wait…the time between the two is different! Yes, that’s because EVs are changing more rapidly than ICE, so we’re at the point where every new release is a big improvement on the previous.

- EVs can help the electricity grid – it’s called V2G, or Vehicle to Grid. In times of peak demand, your EV can power your house. Then, when demand is less, the EV can recharge. And, in the event of a power outage, your EV can act as your electricity supply.

- Consider ICE partial replacement costs. If you run an ICE for 200,000km you won’t need to replace the engine…but you may well need to rebuild it, and will certainly have replaced many parts of it along the way. Starter motor, alternator, spark plugs, fluids, belts, pulleys, tensioners not to mention the transmission. With an EV any battery replacement cost, if it is needed at all, would be nothing for years, then a lot in one go, whereas with ICE the component replacement costs are smaller but more frequent.

- Interstate trips not yet as easy as ICE – if you do need to go further afield, DC fast chargers are becoming ever more plentiful. But, interstate trips in an EV are simply not yet as quick and easy as an ICE trip. EV enthusiasts would beg to differ, but they’d have plenty of time to think about it during their trips. The longer the trip, the more remote and the heavier the load, the greater the difference between EV and ICE. So a Tesla driver that stops once for a supercharger on a freeway between Melbourne and Adelaide isn’t really any slower than an ICE if the latter has a long stop, but a run through rural NSW for example would be signifcantly slower – I’ve done the trips. The stops on a long trip should be dictated by the need of the driver, not the machine, and right now, that’s not the case with EVs.

- Fuel security. Australia has around 2 weeks worth of fuel at any one point. Basically, we are entirely reliant on a steady stream of oil tankers arriving at our shores. All an enemy need do is stop those tankers and we’re stuffed. Electric vehicles would mitigate that risk.

- We won’t “brown out” the grid if “everyone suddenly switches to an EV”. Firstly, EV adoption won’t happen overnight, secondly it’s easy to schedule charge EVs overnight when it’s off-peak and there’s surplus capacity. However, there could well be localised power supply issues just as there are today, although the EV load is a small percentage of the total required compared to say industrial. More on that one here:

- Half of the world’s lithium is mined in Australia, not overseas. Historically, the process hasn’t been very environmentally friendly but that’s changing. If you were wondering about slave/child labour, that’s mostly cobalt in Africa…and things are changing there too. Also, that child labour issue is hardly confined to mineral mining.

- Copper production is critical to EVs as copper is one of the best conductors – an EV uses more than double the copper of an ICE, according to Reuters, or three times according to other sources. EV charging infrastructure also relies on copper, so there’s got to be enough supply to meet demand. I’m not clear on whether that’s possible or not.

- EVs are too complex. No, they’re not…they’re far simpler and even have fewer computers than any ICE vehicle. Much less to go wrong. It is modern cars that generally are complex due to safety, driving aids and convience features, not specifically EVs. There’s a LOT of complexity in the modern ICE just dedicated purely to emissions controls; think EGR, DEF, cats, idle-stop and more, let alone the massive complexity of the ICE itself.

- Australia has a lot of off-street parking which is ideal for charging EVs as the cable doesn’t get in the way of the public, as compared to European city or even suburb dwellers. However, for inner-city residents at-home charging is a challenge. I would find it a major pain to own an EV if I couldn’t charge it at home whilst I slept.

- “But transport is only 24% of the world emissions, and cars are only 13%” or similar. Sure, it’s wrong to claim that if we switched to EVs overnight the world’s emissions problems would be solved, far from it, despite what the some may claim. But every little bit helps, and cars tend to pollute where humans live, with consequent effects on health. So the effect of reducing car emissions is, from a health perspective, greater than the percentage of emissions would suggest.

- EV fires are dangerous. Yes they are, and they can be worse than ICE fires but there is evidence to suggest EVs are less likely to catch fire in the first place. I have covered the topic of EV fires extensively in this interview.

- What about hydrogen? That’s got a lot of advantages relative to electric, namely greater energy density (weight/volume of fuel per km driven), which means greater range and quicker refuelling so it is arguably one part of the future. However, generating hydrogen takes a lot of energy, and then it needs to be transported. My view is that hydrodgen will be limited to uses where battery vehicles can’t (yet) work; that would be long range, quick fuelling or operation of very large vehicles is essential, for example long range towing, offroad touring, trucking, and round-the-clock vehicle operation. As battery tech improves, there will be less and less hydrogen use.

- EV resale? A current dream of the EV crowd is that the resale value of ICE vehicles will dramatically drop as EVs take over. As ever, there’s nuance here. I’m really not convinced because a) EVs cannot replace all vehicle classes any time soon, e.g. diesel 4X4s, b) there is a massive emotional attachement to ICE vehicles and c) the average car-buyer consumer needs to understand and trust EVs, and that buyer isn’t there yet. The ICE cars most likely to be hit for poor resale will be the cheap runabouts that nobody cares about that can be replaced by EVs right now; small SUVs. Vehicles like sports cars and some 4x4s will be worth lots of money for years to come, but how much they can be used on the road in 30 years time is a question!

- Did you know? Less than 2% of the new cars sold in Australia in 2020 were electric, but in Norway it’s more like 75%. In 2022, we’re looking at 4% plus EVs.

And think about this. We’re switching from petrol chainsaws and mowers to electric, and from cord power tools to cordless. I never want to use a petrol chainsaw or mower again, and no longer own either. All that is driven off improved battery technology, and cars are no different.

Here’s a look at EV vs ICE using the Kona as an example, complete with cost comparison:

And this one takes a look at EV charging.

Finally, Tesla recently set the first official EV lap record at the Nurburging. In this video I compare that lap against the one set by a pre-production Porsche Taycan, and a BMW M5 CS to give an ICE comparsion.

Worried about EV 4x4s? Watch this:

4 Comments

by SteveP

I understand these points ar especific to Australia, but #1 needs to be looked at more broadly. Not everyone has a driveway so flat dwellers may have issues. I keep one vehicle in a nice, dry underground garage under a flat with zero access to electricty. For a worst-case scenario, New York City has fewer than 100 public EV chargers. A vast majority of the population lives in flats with no easy way to charge an EV. Household mains power is 120VAC (15A usually) which is totally inadequate for EV charging. So EVs work well and be an easy transition for some drivers in some locations but huge impediments to uptake exist elsewhere

by Chris Carr

While the writer pays grace to both sides of the ‘argument’ he is clearly an EV proponent masquerading as balanced. This is all in the name of saving the planet. One simple question : can the writer please explain to his readers how CO2, an original trace gas critical to most life on earth when slightly increased (but not as much as past natural earth cycles), has suddently become a planet destroying poison? To such a degree that every civilisation must uproot how it operates and cede massive power to international interests? Very interesting indeed.

by Robert Pepper

The CO2 discussion is outside the scope of what I do which is automotive. There are many, many explanations about global warming which cover it and I’m not going to add to them.

by Chris Carr

I’m sure the writer follows his own advice….below…..and does not select which subjects this advice applies to.

“Ask why, and why and why. A true expert will be able to explain things from first principles, and doesn’t ask you to take things on trust. And they’re happy to show their depth of knowledge, and importantly, they often say they don’t know, or offer two points of view. But someone who doesn’t know the true answer will quickly run out of explanatory depth, and be left saying “well that’s the way it is” or telling you it doesn’t matter, or referring to some authority “because they said” which means they don’t understand, they’re just repeating something, often with unwarranted conviction. And they won’t generally consider alternative views.”