What is NVES? Why you’ll be paying more for non-electric vehicles

Here’s the TL;DR. The federal Government has passed a new emissions scheme, the New Vehicle Efficiency Standard, which sets emissions targets for all new vehicles under 4500kg. Vehicles are split into Type 1, which is roughly roadcars and light offroaders, and Type 2 which is utes and heavy offroaders. If a vehicle does not meet its emissions standards then a financial penalty is payable unless the manufacturer can offset it.

As an example, in 2025 a Ford Ranger 2.0 XLS would meet the target so no penalty, but as the targets get tougher year after year, in 2026 it’d be up for a $602 penalty, assuming it doesn’t improve economy. More examples from 2025 are an LC300 attracting a penalty of $1700, a Mustang 4 cylinder $7300, the V8 nearly $14,000, Subaru BRZ $4000. Jimny is over $3000 as its a Light Offroader, so has to meet the Type 1 roadcar targets. You get the idea. Now those penalties may not translate to price increases as manufacturers selling cars which beat their targets earn credits which are offset against penalties; so for every Mustang Mach E electric vehicle Ford sell in 2025, they get enough credits to sell one V8 Mustang without penalty. Manufacturers may also trade credits, so for example a maker of EVs may sell their credits to a maker of diesel utes, presumably at less than the $100/g normal rate.

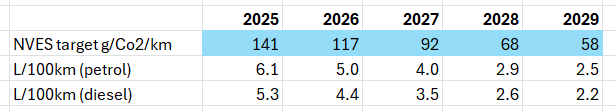

The standards will get increasingly hard to meet over the next 5 years, starting in 2025 at about 7.9L/100km for Type 2, decreasing by about 17% per year till we get to 2029 when it’s 2.2L/100k for Type 1 and 4.2L/100km for Type 2s – the actual standards are grams of CO2 per km, but I’ve converted to L/100km as that’s something people are more familiar with. As you can imagine, no current vehicle nor any future planned could meet these targets, so the only choice is an EV. Anything non-EV would see thousands of dollars added to its price, with subsequent effects on secondhand prices as we saw with COVID.

So by 2029 the Mustang V8 has to handle an additional $22k, the Ranger 2.0 is nearly $8k, LC300 over $11k and even the Nissan X-Trail ePower is $7000. Nissan Y62? Over $21,000. Again, those penalties may not be fully passed on…but it’s hard to see anyone else other than the consumer paying for them.

So why not just buy an EV? For many people that’ll be a great solution, if there’s an EV that fits their use case and they can afford it. But the many readers who drive diesel 4x4s will find there is no EV on the market which can do the job of a Ranger or Prado, and that is the problem with NVES – it will be forcing people into EVs when there aren’t any EVs that can do the job.

Watch this video for the detail, or read on, or both.

NVES in detail

The Government says the reason NVES exists is:

“The primary problem that Government is trying to solve is how to save Australians money on fuel, stimulate the provision of more efficient vehicles into the Australian market and reduce CO2 emissions from new cars”

Having read all of the Government’s documents, I don’t believe that’s a truly accurate representation of the true aim of NVES, and how that statement is written is telling. But we’ll come to that. First:

What is NVES and how does it work?

In brief: every new vehicle in Australia under 4500kg GVM gets an emissions target which will either be beaten or exceeded, earning the carmaker debits or credits. For example, if the target is 200, and the car scores 180, that’s a 20 credit, if it scores 210 that’s 10 debit.

Carmakers total up all the vehicles they’ve sold and if there’s a net debit, they have to pay the Government. So for example if 5000 cars beat their target and earn 2 credits each, that’s 10,000, balanced against 1000 cars which don’t meet target and incur 6 debits each to make 6000, net position 10,000 – 6000 = 4000 debits and that translates into a dollar value.

That’s the summary, but it’s important to dive into detail to fully understand the ramifications of NVES.

The calculations start with categorising every vehicle into a Type 1 or Type 2. Broadly, Type 1 is roadcars and light 4x4s, Type 2 are heavy 4x4s/utes etc – emphasis on ‘heavy’, which we’ll get to, another part of devil-in-detail.

Both Types are given a Headline emissions standard; for 2025 for Type 1 this is 141g/km of Co2, and for Type 2, 210g/km of Co2. We’re more familiar with L/100km, so for Type 1s that target is about 6.1L/100km for petrol and 5.3 for diesel, and for Type 2 it’s 9.1 and 7.9.

But that’s not the target for any specific vehicle. Every vehicle has a different target based on its weight, so an LC300 at 2500kg has a higher target than a Triton at 2100kg. There is a ‘breakpoint’ of 2400kg at which weight no longer matters, so the LC300’s weight is for the purpose of calculations 2400kg.

With the target set, the actual emissions per car as per the NEDC testing cycle are subtracted from the target, and if the actual is greater than the target, a penalty of $100 per gram must be paid or offset.

NVES Ranger Example

Here’s how it works for a Ford Ranger XLS DC 2.0:

- Ranger is a Type 2, so its Headline target is 210g/co2. That equates to about 7.9L/100km as it’s a diesel, but that’s irrelevant for the calculation.

- Its unladen weight (MIRO in NVES terms, which is Mass in Running Order) is 2247kg. Ford doesn’t list MIRO of course, so I’m working off its kerb weight which should be close enough.

- The NVES Reference Weight for a Type 2 car is 2155kg.

- The Government applies a MAF, or Mass Adjustment Factor. Based on that and the Headline, a vehicle-specific figure is worked out. That’s 213g in this case.

- That Ranger’s target is 213g, its actual is 189, so it’s -24g under and therefore earns Ford credits which it can offset against say Raptors or Mustangs – at least for 2025.

What’s the penalty if a car doesn’t meet its NVES target?

The carmaker will have to pay $100 per gram over. So for 2025 in the case of the Mustang V8, that’s 138 x $100 = $13,800 and for the 4 cylinder, $7,300, unless it can be offset.

However, cars that beat their target get a credit, so the Ranger XLS from earlier earns 24 credits in 2025. This means that Ford can sell 6 2.0 Rangers giving them 6 x 24 credits = 144, offsetting the cost of selling one V8 Mustang. A Mustang Mach-E EV has zero emissions (at the tailpipe) so would earn Ford the maximum credits of 141, which is enough for one Mustang V8.

The $100/g penalty will increase year-on-year, that’s written in the legislation, tied to the Consumer Price Index.

That’s 2025, how do the NVES targets change over time?

Here are the emissions targets in g/co2 per km, which I’ve converted to approx L/100km so they are easier to understand:

Type 1 – roadcars & light 4x4s

Type 2 – heavy 4x4s

So in 2026, the target for diesel 4x4s classified as Type 2 will be 6.8L/100km on the combined cycle; anything more gets a penalty at the rate of $100 per g of CO2 per km, or roughly $250 per extra L/100km on top of what you see above. And in 2027, it’ll be 5.7L/100km, anything over will be a penalty.

What could manage 2.5 L/100km? Nothing I can see at this stage – about the most fuel-efficient vehicle on the market is the Yaris hybrid at 3.8L/100k, and even that will fail in 2028. The Camry Hybrid is at 4.7, so that’ll attract a penalty from 2027 onwards.

Light Offroaders : Jimny, Tank 300, Wrangler – caught as NVES Type 1s

Anything categorised by the road rules as NA or NB1 is a Type 2, which is essentially utes and vans. The classification MC is for 4×4 offroad vehicles, but NVES splits that between Type 1 and Type 2.

An MC classed vehicle is Type 2 if it can tow more than 3000kg AND has a separate chassis. Otherwise it’s a Light Offroader, and that’s Type 1.

This means as the Jimny, Wrangler and Tank 300 cannot tow 3000kg they are Type 1s, so gets the higher target of Type 1. The Raptor can’t tow 3000kg either, but it is a NA ute so it’s a Type 2. Large SUVs such Cayenne, X5, Q7 are Type 1s as they’re either not MC, can’t tow 3000kg, and none are seperate-chassis. Most modern Land Rovers (sorry, JLRs) are caught as Type 1 as they’re not seperate-chassis.

The Jimny is light at 1075, so its target is set very low, and unfortunately it has an inefficient engine, poor aero and prehistoric transmission, so its emissions are high meaning in 2025 it would a penalty of $5,996. The lower breakpoint of 1500kg kicks in though, so it’s actually only $3,178.

Effect of NVES on Sports Cars

Goodbye to petrol sports cars. If normal cars can’t meet the NVES standards as they get tougher over the years, then sports cars have no hope as their engines are tuned for performance, not economy, and their tyres are designed to grip, not minimise rolling resistance.

So why don’t we just all buy EV 4x4s?

There’s no way diesel or even hybrid 4x4s are going to meet those targets from 2026 onwards. The only cars in with a hope are EVs. So why can’t we just buy EVs instead of Rangers, Cruisers and Jimnys?

Three reasons. First, there’s too few, second they’re too expensive, and third the energy density of current EV batteries mean they simply don’t have the range and potentially payload required to do the job of diesel 4X4s,and won’t for the foreseeable future. I’ve been analysing this subject for years now, and have done my own comprehensive tests.

The reason payload can become a problem is because batteries are heavy and the bigger the battery, generally the less the payload; the Ford F-150 Lightning is a case in point; the Standard range car has a payload of 1000kg, the Extended range 885kg. As a further example, EV truck makers want legal front axle limits raised from the current 6000-6500kg to 7500kg to accommodate EV trucks.

The only EV 4×4 in Australia is the F-150 Lightning which is $250k plus onroad with a claimed range of 515km and the only other ute is the 2WD LDV which can tow only 1000kg with a claimed range of 330km. There are no 4×4 wagons, and only other notable vehicle is the Kia EV9 SUV (not an offroader) which can tow 2500kg. Overseas there’s the likes of Rivians and Chevys, but fundamentally even if they were here now, they would be too expensive and too short-ranged. We also need to consider that Australia is a RHD country, which means significant additional cost for any EV maker, and that cost cannot be readily amortised over the larger RHD markets like the UK and Japan as both have small 4×4 markets, which is one reason Rivian isn’t here already and the F-150 is being converted by a third party, not Ford.

So let’s look at range; taking the F-150 for example; it’s claimed range with the Extended battery of 131kWh is 515km. We know that real-world use will be more like 400km, maybe 450km to be generous. But that’s the stock vehicle. Working and recreational vehicles are modified with things like offroad tyres, roofracks, service bodies, suspension lifts, offroad tyres, driving lights, winches and so on. Each of those mods adds weight, but more importantly for EVs, drag. So that 450km becomes more like 350km. Then add a trailer and numerous tests, including my own, show range may well drop by 50% towing a decent-sized trailer so you’re down to maybe 200km…to recharge a large 131kWh battery probably to 100% because you need every last kWh, as opposed to the smaller roadcars like Teslas which only need to go to 80% of their say 70kWh battery to dash to the next fast charger.

Consider also the immense popularity of long range diesel 4×4 fuel tanks. I’ve got 140L in my Ranger, up front the standard 80, and many others also buy such tanks, even Toyota owners who get around 120-150L of fuel tank capacity standard in Australia. There’s a reason we spend good money on such fuel tanks.

Other than range, EV 4x4s are great; quiet, lots of storage room, quick, great towcars, capable offroad, reliable, and carry a huge battery which is extremely useful for both recreational and professional users – I love the idea of an EV 4X4! But we need a step-change in battery tech to deliver much better energy density before the EV 4x4s can replace diesels, and also a huge, huge investment in charging. Nissan have just announced their plan for a solid-state battery…in 2028.

When you have a lot of caravanners or holidaymakers in one place you can simply send the diesel tankers twice a week instead of once a month, but with EVs you must invest in huge amounts of charging infrastructure which lies idle until peak times. That’s just one infrastructure problem.

Even the arrival of Ranger hybrid and electric 4×4 utes from Kia, BYD, GWM, Isuzu and others won’t solve the range problem as their technology will still use the same heavy batteries, and I doubt they’ll be as affordable as diesel equivalents either…unless NVES forces the issue.

Which carmakers will be affected most by NVES and why?

To answer that we can roughly categorise the camakers into three:

- WINNERS: NVES is great news for EV makers as their cars will be proportionally cheaper than petrols and diesels, so Tesla, BYD, Polestar etc.

- MAYBES: if a carmaker has the bulk of its sales as low-emissions vehicles, with a few higher-emissions vehicles then it could more or less break even on NVES. Hyundai is an example here with no 4x4s and a strong EV range, but it’ll need to lose its petrol-powered performance car range and transition it to electric, as it has already started with the IOINIQ 5. Audi, Mercdes and BMW may also be about neutral as their cars are already efficient, no real 4x4s or utes, and increasingly strong EV products.

- LOSERS: the clear losers are the carmakers who have high-emitting vehicles only or mostly, such as INEOS, Ram, Isuzu and even Fuso, makers of the Canter light truck which can be rated under 4500kg.

Are the Goverment’s claims about NVES true?

Let’s go back to the stated objective of the NVES:

“The primary problem that Government is trying to solve is how to save Australians money on fuel, stimulate the provision of more efficient vehicles into the Australian market and reduce CO2 emissions from new cars”

Breaking it down:

- Saving money on fuel is pointless if your new or secondhand car costs a lot more, and NVES will increase the cost of almost all non-EV cars to the manufacturer which is likely to be passed on to the consumer, with consequent effects on secondhand values just as we saw with COVID. Notably, that’s the first objective. I believe the fuel saving is put first as it sounds good.

- “More efficient vehicles” – that’s a method, not the purpose. You need to look at whole lifecycle, not just tailpipe emissions.

- Reduce CO2 – this I agree with, that should be an objective for every nation on earth.

So now here we come to the point of the NVES in my view:

To force Australia into EVs as soon as possible.

which is not the same as lower CO2 emissions. My evidence for this statement is:

- The targets become near-impossible to meet unless the car is an EV.

- There is no consideration for those vehicle users who have needs not met by EVs, now or the future.

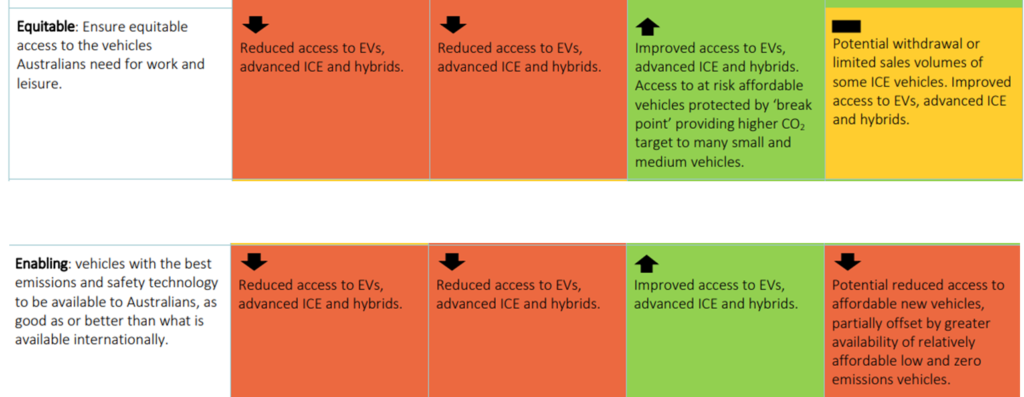

- The Government’s own words. Their consultation paper spoke of two objectives, Equitable and Enabling, both about access to vehicles. Yet if you look at the analysis, it’s all about EVs. Here it is:

To me, that reads like “how do we get Aussies into EVs” not “how we ensure Aussies get the cars they need with as low emissions as possible.

And again from the earlier consultation paper:

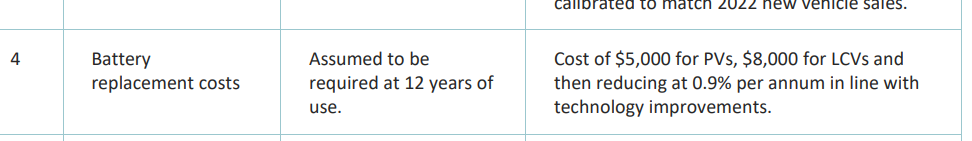

EV batteries may not need replacing at 12 years, but they will at some point and the cost is nowhere near even $8000. If that is the quality of data this is built on to cost-justify it, then I’m concerned. Same for the $108 billion claimed for fuel saving; that’s till 2050, so over 25 years, and assume 21 million motorists – comes out at around $216 per motorist per year, assuming you actually get a more fuel-efficient vehicle. But the big number is impressive until broken down.

Bottom line: what does NVES mean for you, the Aussie car owner?

If your motoring needs cannot be met by an EV, and that will be the case for almost everyone who uses a 4×4 in Australia to tow or tour offroad, then you can expect to pay more for your new car with a consequent increase in secondhand prices too.

Your options are:

- Just pay more for your non-EV.

- Buy an EV and do what you can with it, limited by your budget and the car’s range; this would be severely range-limiting and for the foreseeable future, charging chaos at popular holiday spots.

- Wait for the tech to improve to the point where EV 4x4s have the same range & recharge as diesels. I can’t see that happening any time in the next 3 years, maybe longer, and new tech has a habit of costing a lot.

You may well also consider buying your new car now, or in 2025, rather than waiting some years when NVES will really hurt.

We do need to lower emissions, but forcing people into vehicles that are not fit-for-purpose is not the way to do it, particularly when passenger vehicle emissions are only 10% of the total and NVES would lower that figure but not reduce it to zero. EVs are great for suburban runabouts, and can do longer trips, so by all means incentivise people to buy them for those purposes, but only extend the incentives to other use cases when EVs can do the job.

Personally, I think a NVES is good in principle and I do support lower emissions, but this one is exclusionary and forces people away from cars with nowhere for them to go. “Because other countries have an NVES” is a weak argument which ignores the type of NVES and the differences between each country, and the “it didn’t force up car prices overseas” doesn’t work either as if you look at the data cited, yes there was a net decrease, just, but the cost of 4x4s & SUVs went up by a long way and that’s the problem – nowhere to go if you need one of those.

If you want a decent analysis from a dealer perspective, or a second opinion, read this from Sam Venn who comes to much the same conclusions I do. Here’s an excerpt:

“There is very little pipeline of fit-for-purpose BEVs to replace their higher emitting LCV siblings, the most popular in Australia. Vehicles required to tow or be used as work vehicles do not have near-term BEV replacement alternatives, and risk being removed from the market altogether due to the anticipated cost impact of these vehicles, based on projected consolidated emissions of total OEM sales.“

Here’s the video on NVES: